Master Juba - Inventor of Tap Dancing

Master Juba

The Inventor of Tap Dancing

The Inventor of Tap Dancing

Master Juba's real name was William Henry Lane. He was born a free black man in Rhode Island in 1825, and began his career as a performer in minstrel shows. He played the banjo and the tambourine and could imitate the moves of all of the best dancers of his time. Later he created his own innovations and danced his way to international fame.

In 1842, the great English novelist Charles Dickens toured the United States and wrote a book about it called American Notes. He described a visit to Almack's, a dance hall in Manhattan's notorious Five Points, and a dancer by the name of Master Juba:

"The corpulent black fiddler, and his friend who plays the tambourine, stamp upon the boarding of the small raised orchestra in which they sit, and play a lively measure. Five or six couple come upon the floor, marshalled by a lively young negro, who is the wit of the assembly, and the greatest dancer known."

"Single shuffle, double shuffle, cut and cross-cut; snapping his fingers, rolling his eyes, turning in his knees, presenting the backs of his legs in front, spinning about on his toes and heels like nothing but the man's fingers on the tambourine; dancing with two left legs, two right legs, two wooden legs, two wire legs, two spring legs - all sorts of legs and no legs - what is this to him?"

"And in what walk of life, or dance of life, does man ever get such stimulating applause as thunders about him, when, having danced his partner off her feet, and himself too, he finishes by leaping gloriously on the bar-counter, and calling for something to drink, with the chuckle of a million of counterfeit Jim Crows, in one inimitable sound!"

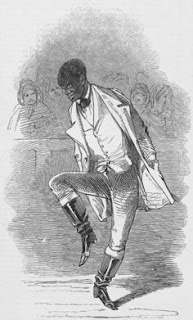

Engraving from American Notes by Charles Dickens (1842) showing Master Juba being observed by Dickens and an associate.

Minstrel Shows

Minstrel shows began in the US in the 1830s, when working class white men (usually Irish) blackened their faces with burnt cork and dressed up as plantation slaves while imitating black music and dance and speaking in a "plantation" dialect. The shows featured a variety of jokes, songs, dances and skits that were based on the ugliest stereotypes of African American slaves. From 1840 to 1890, minstrel shows were the most popular form of entertainment in America and they only died out completely in the 1950s with the advance of civil rights.

Only white actors were allowed to perform in minstrel shows until 1838, when Lane began performing minstrel acts, but even he was required to wear blackface makeup. It seems absurd now to think of a black man being forced to wear makeup so he can look like a white man made up to look black, but that was the only way he was allowed to perform. In the early years of minstrel shows, white audiences simply would not tolerate an actual black man on stage, but Juba's enormous talent made him so popular that he was soon able to perform in his own skin.

Juba and Jude are common slave names that were often adopted by dancers and musicians. Juba is also the name of a supernatural being in some American Black folklore and became the popular name for a prolific weed; the Juba's bush or Juba's Brush.

Minstrel shows began in the US in the 1830s, when working class white men (usually Irish) blackened their faces with burnt cork and dressed up as plantation slaves while imitating black music and dance and speaking in a "plantation" dialect. The shows featured a variety of jokes, songs, dances and skits that were based on the ugliest stereotypes of African American slaves. From 1840 to 1890, minstrel shows were the most popular form of entertainment in America and they only died out completely in the 1950s with the advance of civil rights.

Only white actors were allowed to perform in minstrel shows until 1838, when Lane began performing minstrel acts, but even he was required to wear blackface makeup. It seems absurd now to think of a black man being forced to wear makeup so he can look like a white man made up to look black, but that was the only way he was allowed to perform. In the early years of minstrel shows, white audiences simply would not tolerate an actual black man on stage, but Juba's enormous talent made him so popular that he was soon able to perform in his own skin.

Juba and Jude are common slave names that were often adopted by dancers and musicians. Juba is also the name of a supernatural being in some American Black folklore and became the popular name for a prolific weed; the Juba's bush or Juba's Brush.

Master Juba

The Juba Dance

Most American slaves came from cultures in Africa that had relied on drumming as a means of communication and personal expression. Slaves were not allowed to play drums, so they began to use their bodies as instruments. Over time, the hand clapping, foot stomping, body thumping and thigh slapping evolved into a dance called "patting juba."

Lane combined patting juba with the jig and reel dances that he had learned from his poor Irish neighbors, and added many other ethnic dance steps he had learned, such as the shuffle, the slide, buckdancing, pigeon wing, and clog into a new dance that became known as tap dancing. As his reputation grew, the promoters began to call him Master Juba; the "Dancinest fellow ever was" and he was proclaimed the greatest dancer of all time by American and European writers alike.

Caricature of Master Juba from the 1848 theatrical season

In 1848, a London reviewer gushed:

There never was such a Juba as the ebony-tinted gentleman who is now drawing all the world and its neighbours to Vauxhall. Such mobility of muscles, such flexibility of joints, such boundings, such slidings, such gyrations, such toes and such heelings, such backwardings and forwardings, such posturings, such firmness of foot, such elasticity of tendon, such mutation of movement, such vigour, such variety, such natural grace, such powers of endurance, such potency of pastern, were never combined in one nigger. Juba is to Vauxhall what the Lind is to the Opera House.

There never was such a Juba as the ebony-tinted gentleman who is now drawing all the world and its neighbours to Vauxhall. Such mobility of muscles, such flexibility of joints, such boundings, such slidings, such gyrations, such toes and such heelings, such backwardings and forwardings, such posturings, such firmness of foot, such elasticity of tendon, such mutation of movement, such vigour, such variety, such natural grace, such powers of endurance, such potency of pastern, were never combined in one nigger. Juba is to Vauxhall what the Lind is to the Opera House.

Fame and (relative) Fortune

In 1845, Juba was the first black performer to get top billing over a white performer in a minstrel show. Master Juba competed in many dance contests and defeated all comers including an Irishman named Jack Diamond, who was considered the best white dancer. Juba and Diamond were then matched against each other in a series of staged tap dance competitions throughout the United States.

Juba went on to give command performances before the crowned heads of Europe. The Illustrated London News asked, "How could he tie his legs into such knots and fling them about so recklessly, or make his feet twinkle until you lose sight of them altogether in his energy?" Juba eventually settled in London where he performed with an English dance company and opened his own dance studio.

Throughout his brief career, Juba worked both night and day and it began to take a toll on his health. For most of that time his diet consisted of little more than fried eels and ale. The poor diet, odd hours, and strenuous physical exertion finally caused a breakdown.

William Henry Lane died in 1852 at the tender age of 27. One commentator smugly opined, "Success proved too much for him. He married too late (and a white woman besides) and died early and miserably." But the critics, promoters, theater owners, and his fellow performers mourned his passing, and his legacy was secure then as now. All tap dancers today acknowledge Master Juba as the creator of tap and celebrate his many contributions to modern dance.

Buy a No Soliciting Sign

That Really Works!

Buy Will Write for Food T-shirts!

Copyright © 2024

Ken Padgett

All Rights Reserved.

Reproduction, transmission, or storage in a data retrieval system,

in whole or in part, for other than personal use is prohibited.

Comments

Post a Comment